She clearly didn’t know that this overdose was different. This time, he was dead.

In the emergency department (ED), we’ve become all too familiar with the twenty-something code-blue patient – usually male, often found at the train station around 7:30 am.

The medical management of a cardiac arrest was familiar, but seeing it happen outside of the emergency department, in a patient’s home, I felt uneasy. His name, I learned, was Jonathan; his girlfriend’s name was Chloe. Jonathan’s Eagles jersey tacked to the wall, his university ID on the table, the muted South Park episode still running on his TV – these small snippets of normality made him unlike the John Doe overdose patients I’m used to. They presented a person with a life and a story – a story that would end here. Now.

After twenty minutes of CPR, we stopped. Chloe, still in her pajamas, paced frantically.

“I’m sorry, we couldn’t save him,” the lieutenant told her gently. She collapsed and let out a shriek that rattled the thin walls. Neighbors opened their doors, their faces heavy with expressions of concern or judgment.

“This can’t be happening …. This can’t be happening,” Chloe gasped. “Why didn’t you take him to the hospital? Can you please try something else? Anything else?”

I had no words of comfort to offer. I listened and nodded as she tried to bargain.

A few eternal minutes later, Jonathan’s parents arrived.

Their faces were drenched in sorrow, but not surprise. It seemed they’d been expecting this day – dreading its arrival. Reluctantly, I accompanied Jonathan’s mother into the apartment as Chloe stayed behind, pacing and sobbing.

“What have you done, Jonathan?” his mother wailed, kneeling to embrace him, her hands on his shoulders.

When I’m treating patients in the emergency department, I feel some degree of control, even among the dead and dying. In this living room, I was the guest. My role was undefined, and my medical degree felt meaningless. I stood feeling paralyzed by my own futility and watched Jonathan’s mother kiss his mouth, ignoring the endotracheal tube in her way.

When we heard the radio crackle with the call for another code, I slipped out of the room like a halfhearted guest, relieved to finally have an excuse to leave.

This is an abridged version of Dr Utsha Khatri’s 2020 post at pulsevoices.org, with permission.

Commentary

This was used as one of the pieces for reading at the NHS Scotland Bereavement conference in 2022. It was described as tough, almost too real. The juxtaposition of the setting, at home with only the paraphernalia of a normal life, and the impact on even an experienced professional. The tragedy of a wasted life. Helplessness. You can anticipate and recoil from the lasting impact of the experience on all those involved. Guilty relief at leaving.

Further info

- Utsha Khatri is an emergency medicine physician and fellow in the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of Pennsylvania, USA. Her research and advocacy interests center on improving healthcare access and outcomes for socially vulnerable populations, and drug users in particular. She finds that writing is therapeutic.

- Drug deaths are frighteningly high in Scotland, amongst the highest in Europe. Although there was a fall in 2023, the Scottish rate is 2.7 times higher than in England. Drug deaths in Scotland (National Records Office). BBC News on Scottish drug deaths (2023).

- Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh statement on drug deaths in Scotland.

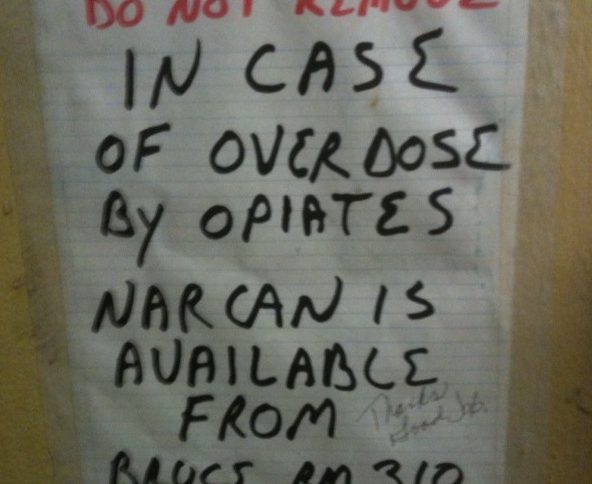

- Image: Peretz Partensky on Flickr

Contributed by

Neil Turner